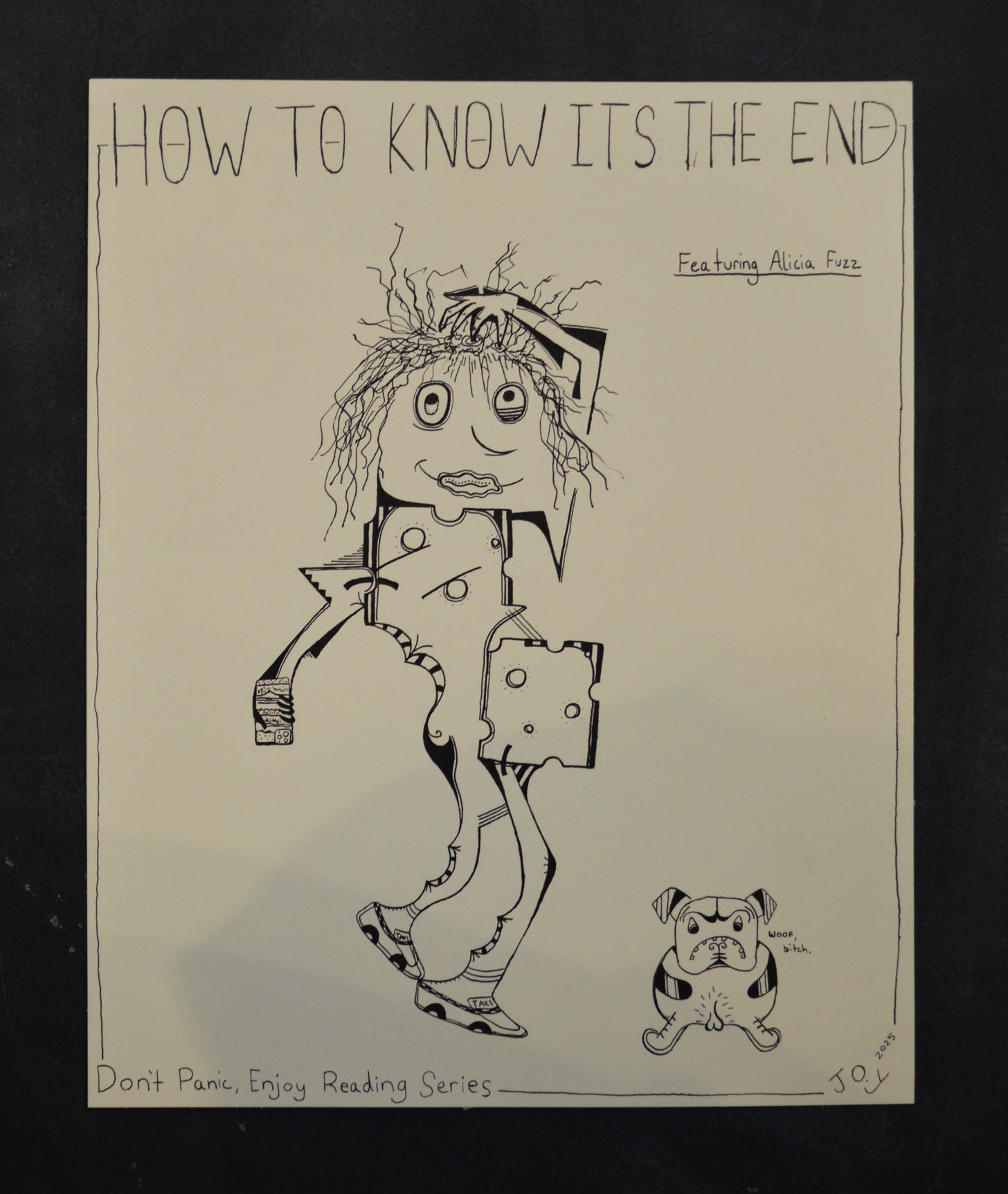

How to Know It's the End

Lydia Riess read "How to Know It's the End" on Sunday, August 24th at the Rudolf Steiner Bookstore.

First there was the problem of her shoes. Ballet flats decorated to look like taxis. These shoes, which normally gave Alicia Fuzz such a distinct and bubbling sense of joy were starting to feel like an embarrassment. She’d always known that the shoes were a bit ironic in the way that all things decorated to look like other things seemed to be winking. Phones that looked like hamburgers. A candle in the shape of a block of swiss cheese. Cake decorated to look like steak, and increasingly, steak decorated to look like cake. At least those little guessing videos still made her happy. Every time the knife would slice through the frosting and sprinkles, revealing a piece of perfectly-cooked meat, she'd be nearly kicking herself. They got me! They totally got me. Yes, that was fun.

But the taxi shoes started to feel less like a wink and more like an eyes-bulging tongue-out sort of ghoulishly-contorted face. A face that thought it was being cute and silly but was actually hard to look at. Alicia Fuzz felt particularly self-conscious on the subway, wearing one form of transportation while riding another. Sometimes she went so far as to try to hide her shoes, crossing her ankles, a fruitless attempt at covering the band of black check riding along the outsoles. Even walking started to gnaw at her. Taxis were for driving. Taxis were, arguably, the opposite of walking. But here she was, strolling around with cars for feet. She didn’t even know how to drive.

She used to love it when people complimented her on the shoes. She’d explain that they’d been a gift from her boyfriend’s mother who ran a consignment store in the suburbs of Maryland and who, upon receiving the shoes into the store, immediately set them aside. “I just thought, ‘Well these shoes are SO Alicia.” That had made her happy at the time. To be known. To be thought of.

But now, when compliments were tossed her way, she couldn’t help but feel like she was secretly being made fun of. To her credit, sometimes the comments really did verge on teasing. Shannon, a coworker, said she liked them because they looked like something out of an illustrated children’s book. “Silly Soozie and her Taxi Shoozies,” Shannon joked. God, some people were so quick on their feet. Maybe that’s what happens when you aren’t bogged down by embarrassing shoes.

But she wasn’t going to just stop wearing the shoes without figuring out exactly what had happened to her or to them to make them fall so drastically out of her favor. So she trudged around, a detective. A detective with her nose in the air. She would have kept her nose on the ground, but she didn’t want the bright yellow patent leather entering her field of vision, so up towards the sky she looked. If this made her a slightly worse detective, so be it.

The next thing Alicia Fuzz noticed, the next thing that seemed strange, was the bulldog outside of the bodega. Balls and all. Balls that stared at you like eyes. Eye balls. She’d seen this dog before but never had she felt so interrogated by its testicles. Now, she had the sense that this dog’s balls were leering. Looking into her soul. And this started happening with all of the unneutered dogs across New York City. She was making eye contact with all of their balls and it wasn’t nice courteous eye contact, a mutual acknowledgement of presence. It was mean. It was a stand-off. Dogs started to seem as if they’d been shooting up steroids. They stood like men, guarding the delis and the bodegas. Watch dogs, with an extra set of eyes below their tails. She hated them. She wondered if this signalled a growing hatred for the male species in general, which might make sense given everything that had happened with Derek. But still, she couldn’t know for sure.

Then there was the butter that had grown mold. Well, not really. The butter seemed as if, maybe, it had grown mold. That or ink from the wrapper, from one of those little tablespoon lines, had bled onto the butter. Regardless, there was a dark spot on the butter. She’d never seen anything like it. Could butter even grow mold? Was butter itself a sort of mold or was that just true about cheese? That was just true about cheese, she thought, and to calm herself down she made a list of things that were true about cheese.

Cheese is mold

Cheese is good for cartoons and candles

Cheese is derivative

Cheese is the first food I ever liked

Cheese, the crumbs, we licked our fingers and dipped our licked fingers into the tub of grated parmesan and sucked our fingers and ate up all the cheese crumbs and called it a meal

There she was thinking about Derek again. Zest for Life. Maybe he really had done a number on her when he told her that if he could choose non-existence he would. It wasn’t that he wanted to kill himself, she knew that and that was good. Still, having it laid out so plainly…

“Sorry,” she’d said. “I just got sad. Thinking about a future together. I want to have a zest for life as I age. What if with you it’s just sad?”

“What?? A zest for life??” he’d replied. “I don’t feel like we’re really zest-for-life people. Do you think we’re zest-for-life people?”

“I mean, yeah. Yes. I’m— well—” Alicia spoke in stops and starts when things were important. “I’m talking about when an actor we like is in a play by a playwright we like and we have to go see it or good food or what about when we traveled around the country and saw all those beautiful things. You’d scream as the car rounded the corner revealing those beautiful vistas. What about those beautiful vistas?”

He thought about it because he was thoughtful when things were important. “If you’re talking about nature, what that really makes me feel is how great it’d be to be an animal and not have advanced thought.”

“Oh. Huh. I guess I didn’t realize that.”

He continued, “But we’d still have all those things. Those zest-for-life things. I just think of them as distractions from life. I don’t think of them as the stuff of life. It’s totally semantic.”

“Okay. Well if it’s just semantic.”

“Yeah. I think it partly is.”

The butter in the fridge smelled like pickle juice and sat next to a jar of pickles, which made Alicia wonder if perhaps pickle juice had spilled onto the butter. Perhaps butter, under normal circumstances doesn’t mold, but this thin layer of pickle juice laying atop the butter had gone rotten, it had molded. Eventually, she spread the butter on a piece of toast, dark spot and all, in a moment of desperation and triumph.

“Hello? Derek?” She breathed into a phone that looked like a hamburger. She’d been conducting a test to see how long it would take her, if ever, to resent speaking into a phone that looked like a hamburger.

“Hi Alicia.”

“Sorry, I know I’m not supposed to be offended but well- I suppose- I’ve just- Part of me feels a little offended. Because well, if you didn’t exist, you wouldn’t have met me and- wait, I know I know. You wouldn't know that you hadn’t met me. You wouldn’t know anything if you didn’t exist and so it’d be okay but still.”

“Yeah. I mean, yeah. It’s not personal,” he offered. She started to cry then. If the hamburger were real, the sesame bun would now be soggy. She was already starting to resent the hamburger phone.

“I just- it makes me sad that I can’t make life worth it for you.”

He laughed then, “Wait I mean, no offense, but of course you can’t make life worth it for me.”

“But see, that’s where we’re different because I think of you as one of the many things that makes life totally worth it!”

He paused. “And I think to me I- well-” She always liked when he spoke in stops and starts because it made her feel like they were equally good at talking. “Well, I think I’d call it a distraction.”

“Okay. Yeah.”

“I will say that I think of love as the greatest possible distraction.”

“Oh. Oh that’s nice. That’s really nice, Derek.”

“So I think this is all very conceptual and semantic.”

The fourth strange thing was her hair. Her compulsion to rip it. This wasn’t like that disorder that starts with a T where you tear out your eyebrows. She never removed hair at the root. Instead she would take her hair, so full of split ends, so in need of a haircut, and slide her fingers down the strands. Little snaps and crackles and pops would erupt, and she’d hold the ends of her hair in her hands, not entirely removed but broken, and broken so easily, in a way that had never before been the case. She’d do this on the subway, dropping inch-long pieces of head hair onto the ground right next to her taxi shoes. She was pleased by the sound and sensation of removing excess. There seemed to be an endless amount of hair on her head that was ready, if not begging, to be gone. That had practically departed already. She was just giving it the extra push, and took so much pleasure in doing so. Plus, she knew she’d be getting a haircut soon enough, so even as the ends of her hair got thinner and thinner, she had no reason to worry.

At some point, though, she developed an intuitive sense that the haircut would mark a very specific moment. It would be a symbolically potent haircut and so she’d been waiting for something big that would pair nicely with it. A break-up or a new job were the most obvious things, followed by a birthday or giving birth. As far as she could tell, none of these were imminent. She took comfort in the fact that in retrospect, the haircut would probably mark something. But in spect, it might just have to be a haircut. She looked into the mirror. Holding onto the ends. Her face surrounded by seven affirmations scrawled on pink Post-its.

I am not offended that my boyfriend would rather be an animal lacking in advanced thought.

I am not offended that I cannot make life feel worth it to him.

I am obsessed with his nihilistic impulses because it means he’s thoughtful and aware.

I love that his head is so far out of the sand that it’s actually in this other place where life is a curse because that’s a place where other really brilliant people go.

It’s not personal. (This one written three times on three separate stickies.)

She asked her reflection, Should I remind him that he is already an animal? No, that wouldn’t help. The lack of advanced thought was the important part, even she understood that. Should I give Derek some kind of spinal injury related to the brain? No. No, probably not.

“Hello, Derek.” She puts the hamburger phone on speaker and speaks in its general direction.

“Hi, Alicia.”

“Derek, I think we have to break up.”

“Why?”

“Well, I need to get a haircut. I need a haircut badly and I need it to mean something. And the butter is molding and I don’t think butter is supposed to be able to do that. When I think about cheese I think about you and that scares me. Did you know that cheese is the first food I ever liked? Dog balls are turning into eye balls. I can’t be sure that any of this has anything to do with you, but I need to check, you know? I need to be sure. Oh, and I’ve been hating my taxi shoes.”

Overwhelmed, Derek does that thing of responding only to the last part of the previous statement, “My mother got you those shoes.”

“I didn’t say I couldn’t be with your mother. In fact, your mother and I are running away together.”

“What?”

“Sorry, that was a bad joke. I just feel a bit lighter all of a sudden. Do you know that I’m speaking to you through a hamburger?”

“No, no, I didn’t realize that.”

“Well, I am. And I’m sorry. And I love you.”

Alicia Fuzz takes scissors to her hair. She is a woman on the subway in taxi shoes. She is a woman on the subway with a bob. She still thinks of Derek when she thinks of cheese, and the dogs still stare. But something is just a little bit better about all of it and this fills her with a distinct and bubbling sense of joy. She thinks about mailing the shoes back to Maryland but decides to write his mother a letter instead. It’s a thank you and an apology, as these things so often are.

Thank you.

I’m sorry.

I’m sorry.

Thank you.

Lydia Riess is a writer, performer, and sometimes director born, raised, and based in New York City. Her original plays include Rocks and Geodes (The Brooklyn Center for Theatre Research), Scorpions Don’t Bite (Providence Fringe Festival), RUFUS (Brown University) and The IKEA Play (The National Theater Institute). She’s been wanting to write more fiction. This is her doing that.